Not Just for Books: Public Libraries Partnering with Police to Engage Communities with Open Data

Available open datasets from law enforcement agencies in the Police Data Initiative (PDI) are becoming increasingly diverse and so too are the partners that help connect police data to communities. Two PDI agencies are leveraging unique partnerships with their local library systems to host police open data and encourage the public’s use of the data. These partnerships are consistent with Pew Research Center findings presented in June of 2016 that confirm that “large majorities of Americans see libraries as part of the educational ecosystem and as resources for promoting digital and information literacy.”

Chattanooga, Tennessee

The Chattanooga Public Library partnered with the City of Chattanooga, the Chattanooga Police Department, and the Open Chattanooga Brigade to provide data online through the library’s website, data.chattlibrary.org, in early 2016, along with other city agencies. The goal of the Chattanooga Open Data Portal is “to give citizens access to community data for solving problems, informing themselves and others, and better interacting with the community around them.” The portal, hosted by Socrata, includes a performance dashboard to track city-wide performance goals, including public safety measures such as reduced domestic violence and violent crime. According to Chattanooga Police Chief of Staff David Roddy the department was driven to place data online because “this is the community’s data. It’s the community’s actions, victimization, response . . . So we need to make that as available and transparent as we can.”[1]

Melinda Harris is a former crime analyst for the Chattanooga Police Department who recently began working on open data for the City of Chattanooga. Harris sees the library as a natural repository for open data “because you’re removing a lot of barriers while providing a neutrality of where the data’s coming from. It isn’t the city pushing data out that only they want, it’s open source coming from the public library.” She also points out that libraries are already the place people go when they are seeking information. “If they need help, the citizens know they can come in and find someone who can help them find the data they’re looking for.”

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

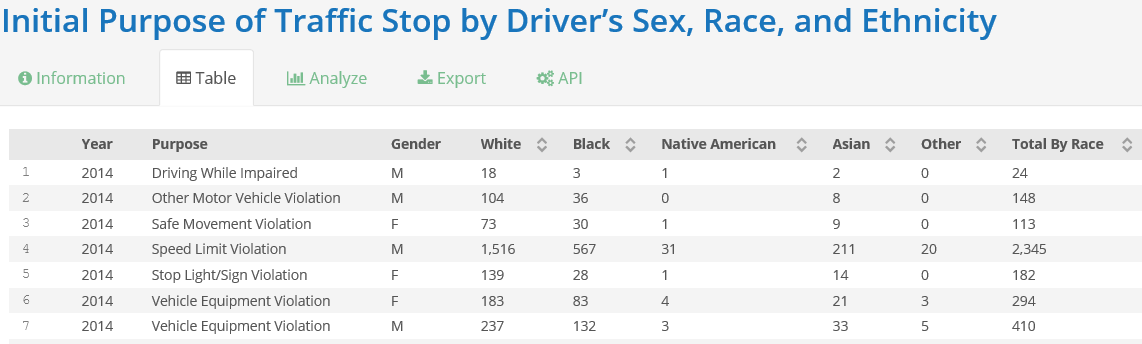

The Chapel Hill Public Library hosts the city’s open data collection at chapelhillopendata.org with the stated objective of increasing “government transparency by facilitating public access to local government information.” Using the OpenDataSoft platform, Chapel Hill began placing data online in 2016. The Portal includes public safety related datasets on agency demographics, traffic stops and bicycle and pedestrian crashes. Community satisfaction survey data is also included, regarding a variety of police department responsibilities and overall satisfaction. Police Chief Chris Blue believes “it’s fantastic to have that information out there. I mean it is our community’s information.”[2] In addition to hosting data, the Chapel Hill Public Library hosted an Open Data Day in January 2017 in order to demonstrate the power of open data, introduce the portal and data to the community, and discuss ways to improve the product with the community.

The drive towards working openness and transparency started before Chapel Hill joined the Police Data Initiative, according to Chapel Hill Police Department Captain of Information Systems Joshua Mecimore. Mecimore says “we were looking for some way to put some of that out there to be transparent, but also to reduce the number of requests we get.” Open data was a way to proactively provide the public with information they regularly requested without them having to ask for it.

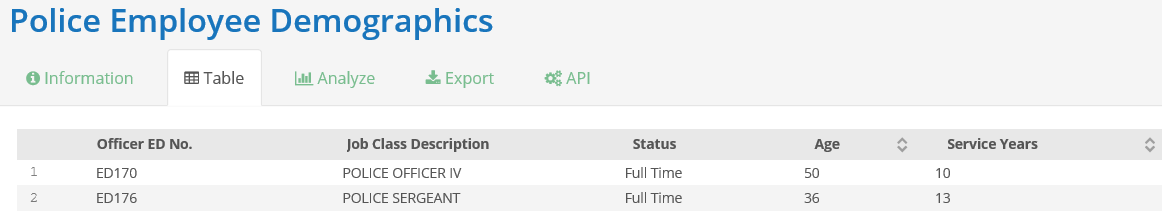

One critical step for the library was helping to make some aspects of the police datasets easier for the public to read and comprehend according to David Green, the Library Systems Manager for the Town of Chapel Hill. Green says that “some of the column headers were acronyms or abbreviations or numbers that might mean something to the department but wouldn't’ mean anything to the public. So we have a conversation with the police about what the data sets are and come up with a vocabulary that both reflects reality and is understandable for the consumers.”

[I]t seemed like a perfect fit - if they were putting out data from town hall and parks and recreation that they would also house the police data.

Captain Joshua Mecimore, Town of Chapel Hill Police Department

As one example, Green points to Chapel Hill’s police employee demographics dataset which initially marked an employee's status as ‘F’ or ‘P’. The library believed that might be confusing for the public and worked with the department to change that to ‘Full Time’ and ‘Part Time’ on the open data portal.

Partnering with the Chapel Hill Public Library was a natural step for the police department. According to Mecimore, the library “wanted to start putting out public data in an open format and began looking for a vendor. They were moving faster than we were so it seemed like a perfect fit - if they were putting out data from town hall and parks and recreation that they would also house the police data.”

Beyond Chattanooga and Chapel Hill…

There are several other public library systems are getting engaged in open data. The California Research Bureau within the state library system, together with Washington State, is developing an open data curriculum that can be used to bring staff and the community up to speed on what open data is and how it can be used by the community. Meanwhile the Baltimore Police Department teamed up with the Enoch Pratt Library last year to announce plans to release civilian complaint and use of force data. Major library associations are encouraging local libraries and librarians to get involved in open data and to embrace its use.

These agencies and their open data partners all demonstrate that there are a multitude of ways that towns and cities can approach open crime and policing data. Law enforcement agencies need not be responsible for all aspects of the open data process, and partnering with libraries or research institutions that are already engaged in open data can be a great way to tackle open data problems.

Post via Police Foundation (@PoliceFound) & Jeff Asher

Top Photo Credit: Chief Christopher Blue, Chapel Hill Police (Photo Courtesy of Chapel Hill Library, Chapel Hill Police Department).

Take-aways:

Are you collaborating with your library to publish police data or engage with the public? Tell us more at PDI@policefoundation.org or find us on Twitter at @PoliceOpenData

If you liked this post, please share!